My Terminal Image Problem

By Raymond Brigleb

in Studio Notes

When I was younger, like in junior high school, pixel art was all there was. Pixel art was computer art. I loved pixel art and I loved thinking about it, probably for similar reasons that I love drawing imaginary maps and inventing configurations for railroad routes.

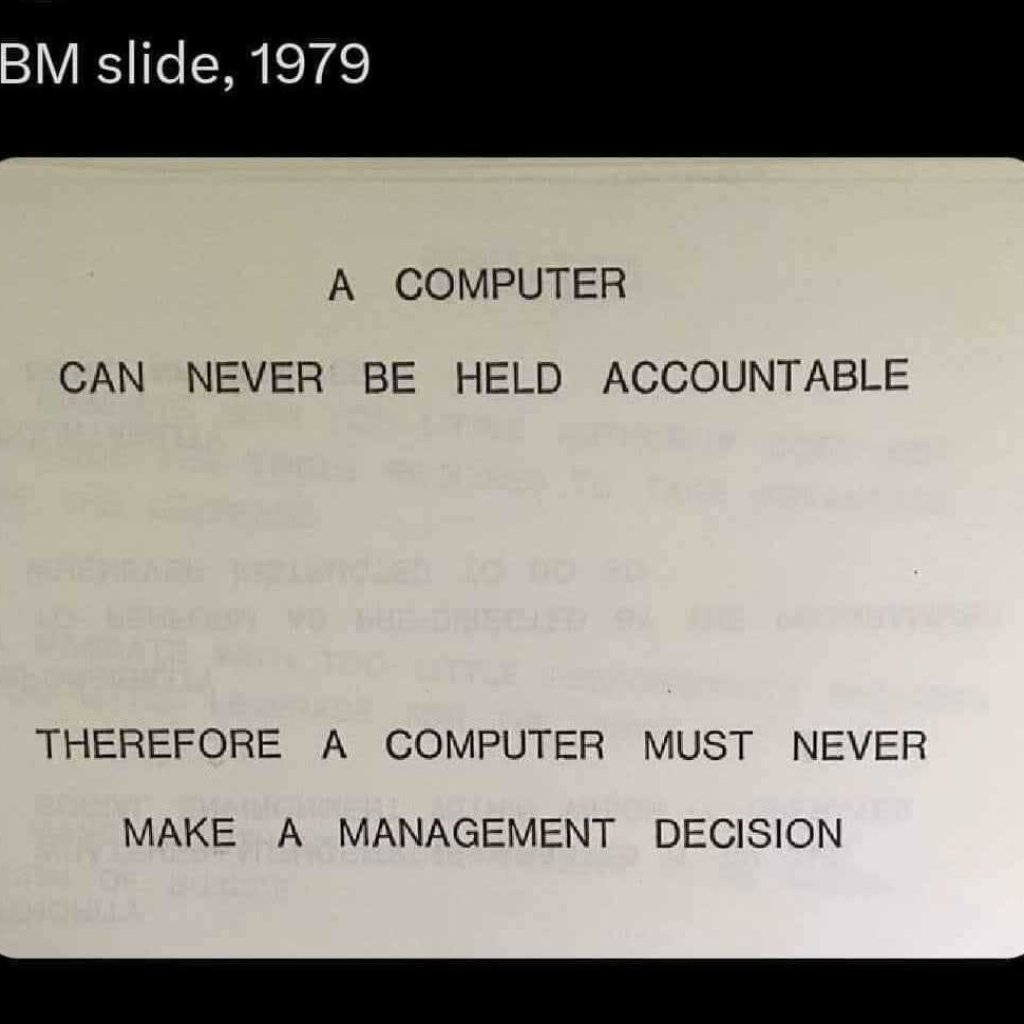

For my final project in computer class in junior high, I made an animation with my friend Adam which required me to fill out pages and pages of meticulously colored-in graph paper and write hundreds of lines of DATA statements containing the X-Y coordinates of each pixel we wanted to draw. This was on a very primitive Apple II computer, so the so-called pixels were either green or black, and this was written in Applesoft BASIC. I think we could only address 40×48 blocks on the screen, which we treated as pixels.

As a grown-up designer, I spend my time making vectors. Vectors are kind of the goal of any designer because they can scale to any size without losing quality—whereas pixel art, of course, does not work that way. Designing for the web was originally a pixel sport, but over time it's become more and more vector-oriented, which is great.

But for all my vector work, I've always spent a lot of time in the terminal. This is the interface anyone around in the '80s would recognize: you type in commands and it runs programs. I do a lot of this because I'm not only the lead designer at our studio but also basically a programmer and IT guy. And I've probably spent more time in the terminal lately rather than less, because I've been using command-line tools like Claude Code.

The way a terminal interface is designed hasn't really changed. It's based on a grid of characters, with every character having the exact same width. While more characters have become available over time—symbols, emoji, and so forth—the premise hasn't changed.

As you type commands, things scroll upward, and the grid is replaced by new grids of characters. You don't think in terms of the pixels that make up the characters. You just think in terms of a grid of characters.

Which doesn't exactly lend itself to graphics.

But I was making a command-line tool and looking for a way to show at least a primitive preview of each image being processed.

Obviously, if I had 10 rows available for the image, I could choose a color for every cell and fill in those 10 rows across, say, 20 columns. But that would be an extremely low-quality image and probably hard to implement. Surely, in this day and age, there has to be something better.

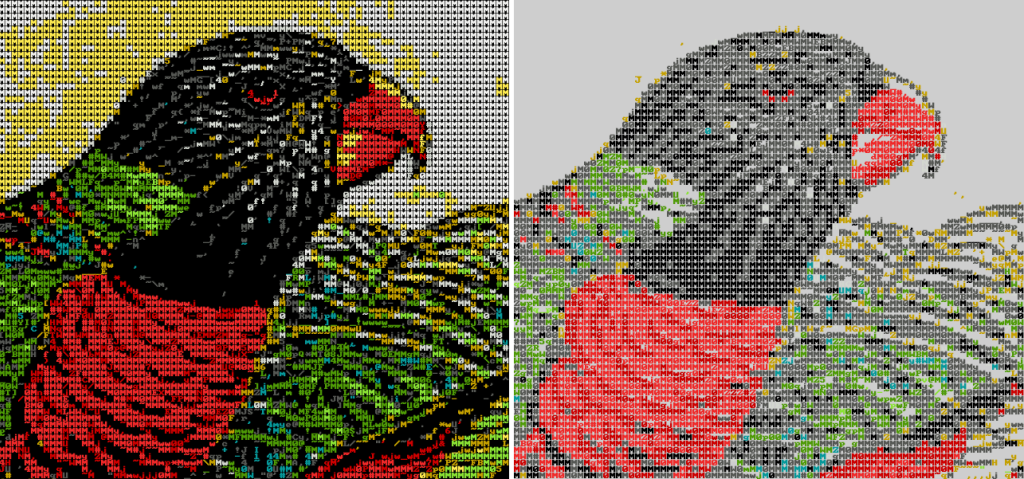

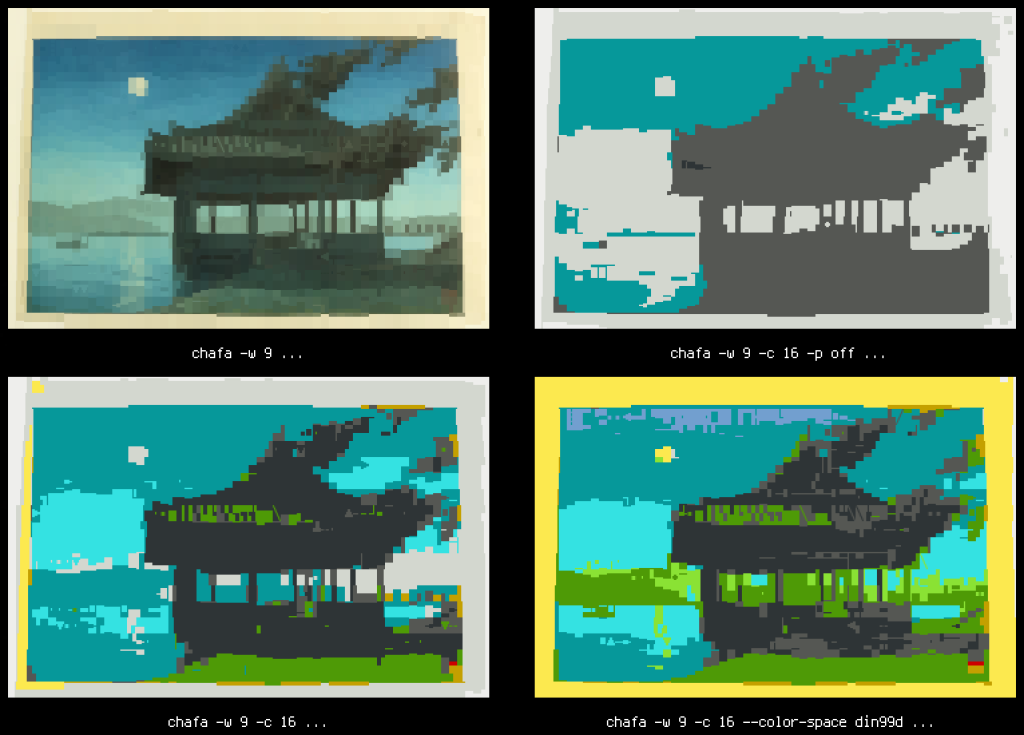

Well, it turns out there is. There's a library called Chafa that handles exactly this: give it an image and a few parameters, and it will output that image as best it can in your terminal. It works great. But how it works is really interesting to me.

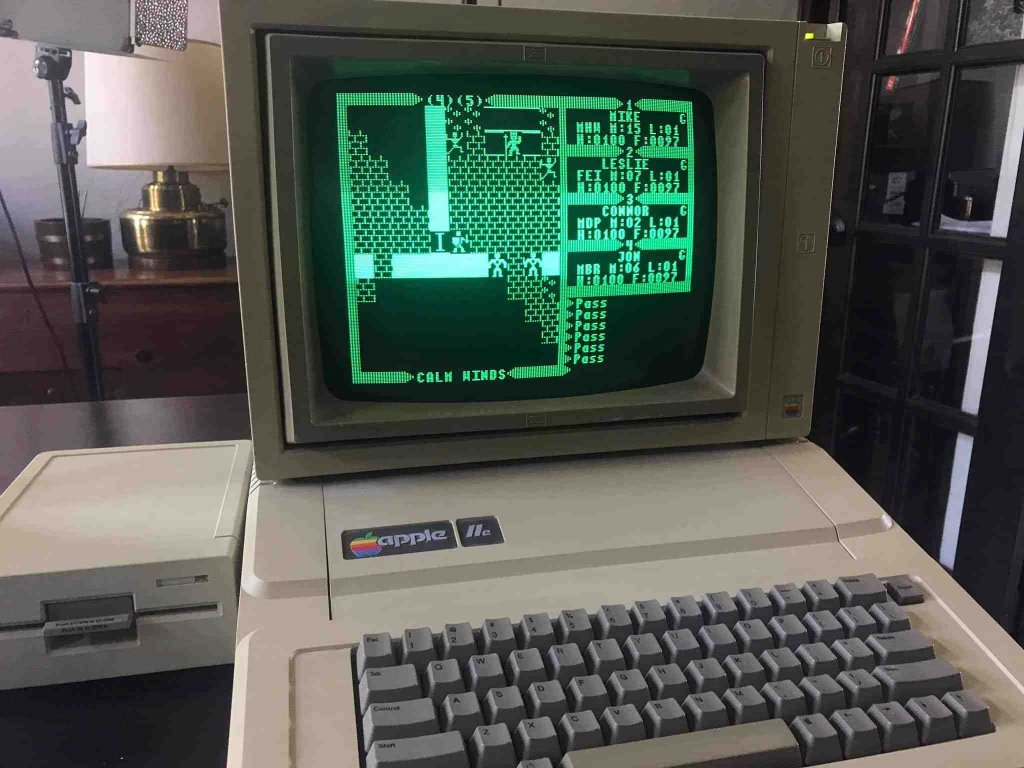

So obviously you could fill in the character cells as I've described. Fine, though quite rough. But on any modern terminal, you can use symbols that fill in half-height blocks—the Unicode block elements ▀ and ▄—which creates a rough pixelated image. Using my example of having 10 rows of text available, this trick effectively gives you 20 rows of pixels. You set a foreground and background color for each character, filling in only the top or bottom half with the foreground color while the other half uses the background. It's a simple trick, but it doubles the vertical resolution. Now we're getting closer to something usable.

But it doesn't stop there. Decades ago, someone came up with a format called Sixels. Sixels—short for "six pixels"—consist of a pattern six pixels high and one wide, giving you 64 possible patterns (2⁶). It basically replaces your character set with a different set that can render primitive graphics. This method was developed for DEC terminals in the 1980s, and it works surprisingly well compared to half-height blocks—quite a bit more detail. Very respectable.

But it actually doesn't even stop there, because some terminal emulators support native image rendering through their own graphics protocols! Kitty has one; iTerm2 has another. I'm not entirely sure how it works at the protocol level, but it outputs an image that is pretty much pixel-accurate in your terminal. If you're using the right terminal app, it looks exactly like a photograph floating by along with all your text.

Best of all, Chafa intelligently uses the best method available. If I run my app in Kitty, I see photo-realistic images. If I use the default macOS Terminal, which only supports half-blocks, they look more pixelated—but still pretty good.

Working on the command line is as useful these days as it's ever been. Fun hacks like this always make it new and interesting for me.

All images courtesy Hans Petter Jansson, author of Chafa.